- Joined

- Oct 1, 2007

- Messages

- 13,643

- Reaction score

- 10,037

- Website

- www.africahunting.com

- Media

- 5,597

- Articles

- 321

The Red Man

John Rigby & Co.'s historic business ledgers shed new light on "Karamojo" Bell.

Bell's Royal Aero Club Aviator's Certificate (his pilot's license) photograph, taken on 15 August 1915. It also shows his birthdate, 8 September 1880, at Edinburgh-actually Uphall, Linlithgowshire, now West Lothian. Royal Air Force Museum.

Some of his African friends called him Longellynyung, the Red Man, but to John Rigby & Co. he was "Bell, WDM, Esq" and a good and steady client. Between March 1906 and September 1945, the firm's daybooks carry 34 pages of transactions with him. Seventeen of those pages record the purchase of guns: seven .275s (including one his father-in-law bought in 1921), a .303, two .350s, two .416s and one .220 Hi-Power, all on Mauser actions; a .303 Lee-Enfield sporter, a 12-bore Rigby ejector double, a Rigby single-shot .250 rook rifle, a take-down .318 on a Springfield action, two more .220 Hi-Powers (one a Savage and the other a Winchester Model 1902 single-shot) and two Colts-a .22 rimfire Police Positive revolver and a Model 1911 .45 semiautomatic.

Bell also ordered cleaning rods and pull-throughs, brushes and solvents, gun oil, repairs and modifications, sights, slings, gun cases and cartridges. Each daybook entry tots up the fees and adds shipping charges-to the Isle of Wight, or to Edinburgh or Garve in Scotland, to Mombasa in the East African Protectorate or Brazzaville in the French Congo, or just "special delivery to docks." Notably, there are orders for "Willesden special canvas cartridge belts."

No one else used such a thing on safari, at least for big game; a vest with half a dozen cigar-size Express rounds was deemed sufficient, and quite heavy enough, thank you. Along with his unusual (for Africa) rifles, these belts are clues to Bell's unique style of hunting for a living. While other white men swore by the "shocking power" of big-bore doubles, Bell killed close to two thousand elephant, hippo, rhino, buffalo, lion and giraffe, and God knows how much lesser game, with precisely placed taps from light bolt-actions. Bell the ivory hunter looked for high volume and efficiency, and low costs as well as low risk. The cartridge belts and the magazine rifles spoke to the first three; study, practice, experience and his own abilities minimized the risk.

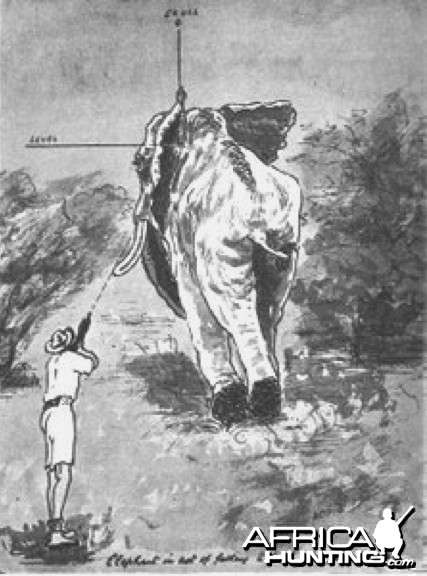

One of Bell's best-known drawings, showing the angles and point of impact for a brain shot on a tusker going away. Bell dissected elephants and sawed up their skulls until he knew exactly how to reach a vital organ from any perspective. He also knew that a small bullet could kill an elephant just as readily as a big one, if it was put in the right spot.

Even at an average of just one and a half rounds per elephant, Bell went through a lot of ammunition. For a while he liked to carry one of his five-shot .275 Rigby Mausers with a 10-shot cordite .303 Lee-Metford in reserve: "I always had hopes that sometime somewhere I would find a bunch of bull elephant so foolish as to stand around while I shot them down and numerous enough for the ten-shot rifle." The reserve rifle took different ammunition, so whenever possible Bell topped up the magazine of his primary rifle in between elephants, which the thumb cut-out on the left side of the Mauser action and the 35-round belt on his hips made easier.

Like the professional buffalo hunters of the American West, he had learned how to approach a herd, which elephants to kill first and how, the effects of weather and so on, in order to drop as many tuskers as possible. Handy, relatively quiet rifles and precise shooting reduced the disturbance. Many times a brain-shot bull slumped to its knees while its mates failed to notice. On a bend in the Nile in northeastern Uganda, shooting in a cold, hard rain and grass eight to 12 feet tall-with a young herd boy carrying his backup rifle and with his cartridge belt full of solids-Bell once dropped 19 elephants. Eleven lay so close to each other that he could step from one to next without touching the ground.

On that occasion, he was using two .318s. That 250-grain bullet, a round-nose solid, had proved to be slightly more effective than the 173-grain .275 (as the Brits called the Mauser 7x57mm) when it came to reaching through the neck for the brain of a going-away bull. Overall, however, Bell used the .275 more than the .303, .318 or .350 simply because German-made DWM 7mm ammunition was so utterly reliable.

When the elegant Model 1903 Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbine appeared, with its 160-grain 6.5x54mm round (dubbed the .256 in Britain) Bell had one delivered to him in the bush, along with a supply of solids. The businessman had to try the latest tools of his trade.

Rigby Mauser No. 4968, sold to Bell in September 1923 as part of a large order for the Forbes safari.

He already had a Mannlicher finished by George Gibbs of Bristol, but just for general use, as he had only soft-nose bullets for it. At the time, Bell had about 150 people in camp-skinners, porters, mule drivers, cooks, askaris and their women and children-"all to be fed on the proceeds of one rifle Not only the needs of the stomach but the need for footwear, for hides for donkey saddles, thongs, and buffalo and giraffe hides for trading flour from the natives all had to be provided by the rifle." Feeding this entourage took nine or ten giraffe, "a score or so of zebra" or a dozen buffalo at a time.

The Gibbs Mannlicher was a "round the clock rifle;" the Schoenauer would be put to work on ivory. Bell's friend Daniel Fraser, the Edinburgh gunmaker, had stocked, finished and sighted it, and it weighed just a bit more than five pounds, empty. Everything from elephants to guinea fowl began to fall to the little jewel. Then one day there came just a dry click! Without looking, Bell ejected the dud and cranked in a fresh round. It wouldn't chamber. The bullet from the misfire had stayed behind and was blocking the barrel. Furthermore, unburned powder had spilled into the action and was binding it up. Keeping one eye on the browsing elephant, Bell set about shaking out the powder, thumping the rifle on the ground and then against a tree to try to dislodge the bullet, and finally searching for sticks skinny enough to go down a quarter-inch bore. That did it, but now the sticks were stuck! Bell had a go anyway, at the body instead of the brain, in case the bullet was deflected. Nothing burst, but at the shot the bull departed at speed. Bell chased him, and his $700 tusks, for miles but it was no use.

One of Bell's pen-and-ink map drawings. This one, of the regions he hunted in West Africa, is filled with anecdotes ("Plutocrats of Niger Delta used to decorate their women with necklets of ivory from large-dia. tusks. Force & palm oil were required. Price per pair ï½£40.") and sketches-his steam-powered river launch, the catamaran houseboat, elephants in the swamps.

So it was back to DWM ammunition and the Rigby Mauser .275s, even if they weighed two pounds more than the little Schoenauer and threw a lighter bullet than the .318.

Upon killing his first elephant, Bell had sawed its massive skull in two in order to find exactly where, and how big, was its brain, and how to slide a bullet past the protective bone into it. He peered into a dead elephant while his askaris pushed spears in from the outside, to learn the angles to the vital organs. He realized that a small bullet could kill an elephant just as readily as a big one, if it was put in the right spot, and much better than a big one in the wrong spot.

Light, compact, balanced rifles had their own advantages: Carrying one himself, and without a sling, instead of handing it to a gunbearer, provided many more hours of handling it, and Bell dry-fired his rifles until they were as familiar as his own hands. He once killed three Cape buffalo in rapid fire, each with one .275 solid. Giraffe, he wrote, with their heads sticking up above the bush, were easy game even at 500 yards. (Bell began to use telescopic sights only when he was in his fifties.) The various .22s he bought from Rigby, rimfire and high-velocity, were meat guns for birds and plains game, even sometimes buffalo.

Ammunition for light rifles was cheaper, too, which appealed to Bell the businessman and canny Scot. In 1913 he ordered two .416s from Rigby; it's easy to imagine that he was curious about this new big-game cartridge that John Rigby had invented for the Mauser. He found that it was no more deadly than his .275s, but heavier, harder-kicking and noisier, and the ammunition cost more than twice as much.

While on break in Jinja, where the Nile flows out of Lake Victoria in Uganda, Bell would go to the shore to plink at cormorants. He had 6,000 rounds of British-made .318 to burn; ammunition that he no longer trusted for elephant. The birds came in over a rock ledge, flying straight but fast and about a hundred yards up. One evening a couple of clerks from the town's colonial office approached him to ask what sort of shotgun he was using-"it kills much better than ours." They were astonished to see that he was dropping the birds with a rifle.

Bell reportedly shot 1,011 elephants with his Rigby .275 rifles, 200-plus elephants with .303s, 300-plus with his Mannlicher-Schoenauer .256 and many more with .318s, .350s, .416s and at least one .450/.400. Overall he probably killed at least 1,700 elephants "to his own rifle," as it was said.

Bell the retired country gentleman, fit and sharp as he approached 70.

In five years of steady hunting between 1902 and 1907, interrupted only by trips to Nairobi to sell ivory and re-stock his supplies, Bell's average tusk weight was 53 pounds and about 10 percent of his elephants had single or broken tusks. Later on, in the Lado, the average weight dropped to 50 pounds. If his career average was just 45 pounds, and if 90 percent of 1,700 elephants had two tusks, that would have amounted to some 145,350 pounds of ivory. In 1907, Bell was paid 12 shillings per pound of ivory, a figure that might also be a reasonable career average. This would put his gross earnings at about ï½£87,000, of which some 30 percent probably went for overhead: travel, ammunition, guns, camp and trade goods and pay for his native crews. Through the 1930s, a working-class family in Britain could live for a year on ï½£150.

Bell's version of R&R was an infrequent trip home, bringing unusual gifts: "Instead of suit cases, the railway porters had nine- or ten-foot-long slippery tusks to handle. They slid off the barrows, and when they did stay put they raked the mob of baggage-seekers just about knee-high, to their indignation. These tusks that I thus brought home were duly presented to my sisters, who promptly sold them and invested in diamonds."

Bell flew rickety fighter planes in the Royal Flying Corps in World War I over Europe and in South Africa, with all the high adventure one might expect and then some. After the war, he succumbed to both marriage and "Balkan malaria," then returned to Africa for a long and profitable safari along the Niger and Bahr Aouck rivers. But the era of the automobile was dawning. A road-narrow, rutted, dusty or muddy, but nonetheless a road-had been cut through the Karamoja. The great days of Africa seemed over to Bell; now the emphasis was on rushing through the bush as fast as possible. He cashed out and went home.

Apparently Bell returned to Africa just once more, in late 1923, to escort two American half-brothers, Gerrit and J. Malcolm Forbes of Boston, on a motorized safari through Chad and Sudan. He had little to say about the trip in his memoirs other than that their car and lorry caused considerable unease among the native tribes and "as for serious hunting, it was out of the question." They went crashing through the bush at 30 or 40 miles per hour!

Bell and his wife Katie retired to a handsome home at Garve, in the Scottish Highlands about 25 miles northwest of Inverness, on Corriemoillie, her family's estate. They commissioned a steel-hulled sailing yacht, a bluewater racer/cruiser to a design by Olin Stephens, and named it Trenchemer, after Richard the Lion-Heart's red galley. The stories and pencil sketches that Bell had begun many years earlier in Africa now became magazine articles and eventually two popular books, and then a third one after his death. Bell the country gentleman sailed and tramped the hills and hunted deer and rabbits, and continued to do business with Rigby in London. The last Bell entry in the company's ledgers reads:

Wednesday Sept. 5, 1945

Capt. W.D.M. Bell / Corriemoile [sic] Garve. Let him know as soon as we are able to fit a new barrel to one of his .275 rifles & quote price. Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley and Roger Sanger

Excerpted with permission of John Rigby & Co. from Rigby: A Grand Tradition, a 2012 book by Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley & Roger Sanger. Available from Amazon and other book sellers.

John Rigby & Co.'s historic business ledgers shed new light on "Karamojo" Bell.

Bell's Royal Aero Club Aviator's Certificate (his pilot's license) photograph, taken on 15 August 1915. It also shows his birthdate, 8 September 1880, at Edinburgh-actually Uphall, Linlithgowshire, now West Lothian. Royal Air Force Museum.

Some of his African friends called him Longellynyung, the Red Man, but to John Rigby & Co. he was "Bell, WDM, Esq" and a good and steady client. Between March 1906 and September 1945, the firm's daybooks carry 34 pages of transactions with him. Seventeen of those pages record the purchase of guns: seven .275s (including one his father-in-law bought in 1921), a .303, two .350s, two .416s and one .220 Hi-Power, all on Mauser actions; a .303 Lee-Enfield sporter, a 12-bore Rigby ejector double, a Rigby single-shot .250 rook rifle, a take-down .318 on a Springfield action, two more .220 Hi-Powers (one a Savage and the other a Winchester Model 1902 single-shot) and two Colts-a .22 rimfire Police Positive revolver and a Model 1911 .45 semiautomatic.

Bell also ordered cleaning rods and pull-throughs, brushes and solvents, gun oil, repairs and modifications, sights, slings, gun cases and cartridges. Each daybook entry tots up the fees and adds shipping charges-to the Isle of Wight, or to Edinburgh or Garve in Scotland, to Mombasa in the East African Protectorate or Brazzaville in the French Congo, or just "special delivery to docks." Notably, there are orders for "Willesden special canvas cartridge belts."

No one else used such a thing on safari, at least for big game; a vest with half a dozen cigar-size Express rounds was deemed sufficient, and quite heavy enough, thank you. Along with his unusual (for Africa) rifles, these belts are clues to Bell's unique style of hunting for a living. While other white men swore by the "shocking power" of big-bore doubles, Bell killed close to two thousand elephant, hippo, rhino, buffalo, lion and giraffe, and God knows how much lesser game, with precisely placed taps from light bolt-actions. Bell the ivory hunter looked for high volume and efficiency, and low costs as well as low risk. The cartridge belts and the magazine rifles spoke to the first three; study, practice, experience and his own abilities minimized the risk.

One of Bell's best-known drawings, showing the angles and point of impact for a brain shot on a tusker going away. Bell dissected elephants and sawed up their skulls until he knew exactly how to reach a vital organ from any perspective. He also knew that a small bullet could kill an elephant just as readily as a big one, if it was put in the right spot.

Even at an average of just one and a half rounds per elephant, Bell went through a lot of ammunition. For a while he liked to carry one of his five-shot .275 Rigby Mausers with a 10-shot cordite .303 Lee-Metford in reserve: "I always had hopes that sometime somewhere I would find a bunch of bull elephant so foolish as to stand around while I shot them down and numerous enough for the ten-shot rifle." The reserve rifle took different ammunition, so whenever possible Bell topped up the magazine of his primary rifle in between elephants, which the thumb cut-out on the left side of the Mauser action and the 35-round belt on his hips made easier.

Like the professional buffalo hunters of the American West, he had learned how to approach a herd, which elephants to kill first and how, the effects of weather and so on, in order to drop as many tuskers as possible. Handy, relatively quiet rifles and precise shooting reduced the disturbance. Many times a brain-shot bull slumped to its knees while its mates failed to notice. On a bend in the Nile in northeastern Uganda, shooting in a cold, hard rain and grass eight to 12 feet tall-with a young herd boy carrying his backup rifle and with his cartridge belt full of solids-Bell once dropped 19 elephants. Eleven lay so close to each other that he could step from one to next without touching the ground.

On that occasion, he was using two .318s. That 250-grain bullet, a round-nose solid, had proved to be slightly more effective than the 173-grain .275 (as the Brits called the Mauser 7x57mm) when it came to reaching through the neck for the brain of a going-away bull. Overall, however, Bell used the .275 more than the .303, .318 or .350 simply because German-made DWM 7mm ammunition was so utterly reliable.

When the elegant Model 1903 Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbine appeared, with its 160-grain 6.5x54mm round (dubbed the .256 in Britain) Bell had one delivered to him in the bush, along with a supply of solids. The businessman had to try the latest tools of his trade.

Rigby Mauser No. 4968, sold to Bell in September 1923 as part of a large order for the Forbes safari.

He already had a Mannlicher finished by George Gibbs of Bristol, but just for general use, as he had only soft-nose bullets for it. At the time, Bell had about 150 people in camp-skinners, porters, mule drivers, cooks, askaris and their women and children-"all to be fed on the proceeds of one rifle Not only the needs of the stomach but the need for footwear, for hides for donkey saddles, thongs, and buffalo and giraffe hides for trading flour from the natives all had to be provided by the rifle." Feeding this entourage took nine or ten giraffe, "a score or so of zebra" or a dozen buffalo at a time.

The Gibbs Mannlicher was a "round the clock rifle;" the Schoenauer would be put to work on ivory. Bell's friend Daniel Fraser, the Edinburgh gunmaker, had stocked, finished and sighted it, and it weighed just a bit more than five pounds, empty. Everything from elephants to guinea fowl began to fall to the little jewel. Then one day there came just a dry click! Without looking, Bell ejected the dud and cranked in a fresh round. It wouldn't chamber. The bullet from the misfire had stayed behind and was blocking the barrel. Furthermore, unburned powder had spilled into the action and was binding it up. Keeping one eye on the browsing elephant, Bell set about shaking out the powder, thumping the rifle on the ground and then against a tree to try to dislodge the bullet, and finally searching for sticks skinny enough to go down a quarter-inch bore. That did it, but now the sticks were stuck! Bell had a go anyway, at the body instead of the brain, in case the bullet was deflected. Nothing burst, but at the shot the bull departed at speed. Bell chased him, and his $700 tusks, for miles but it was no use.

One of Bell's pen-and-ink map drawings. This one, of the regions he hunted in West Africa, is filled with anecdotes ("Plutocrats of Niger Delta used to decorate their women with necklets of ivory from large-dia. tusks. Force & palm oil were required. Price per pair ï½£40.") and sketches-his steam-powered river launch, the catamaran houseboat, elephants in the swamps.

So it was back to DWM ammunition and the Rigby Mauser .275s, even if they weighed two pounds more than the little Schoenauer and threw a lighter bullet than the .318.

Upon killing his first elephant, Bell had sawed its massive skull in two in order to find exactly where, and how big, was its brain, and how to slide a bullet past the protective bone into it. He peered into a dead elephant while his askaris pushed spears in from the outside, to learn the angles to the vital organs. He realized that a small bullet could kill an elephant just as readily as a big one, if it was put in the right spot, and much better than a big one in the wrong spot.

Light, compact, balanced rifles had their own advantages: Carrying one himself, and without a sling, instead of handing it to a gunbearer, provided many more hours of handling it, and Bell dry-fired his rifles until they were as familiar as his own hands. He once killed three Cape buffalo in rapid fire, each with one .275 solid. Giraffe, he wrote, with their heads sticking up above the bush, were easy game even at 500 yards. (Bell began to use telescopic sights only when he was in his fifties.) The various .22s he bought from Rigby, rimfire and high-velocity, were meat guns for birds and plains game, even sometimes buffalo.

Ammunition for light rifles was cheaper, too, which appealed to Bell the businessman and canny Scot. In 1913 he ordered two .416s from Rigby; it's easy to imagine that he was curious about this new big-game cartridge that John Rigby had invented for the Mauser. He found that it was no more deadly than his .275s, but heavier, harder-kicking and noisier, and the ammunition cost more than twice as much.

While on break in Jinja, where the Nile flows out of Lake Victoria in Uganda, Bell would go to the shore to plink at cormorants. He had 6,000 rounds of British-made .318 to burn; ammunition that he no longer trusted for elephant. The birds came in over a rock ledge, flying straight but fast and about a hundred yards up. One evening a couple of clerks from the town's colonial office approached him to ask what sort of shotgun he was using-"it kills much better than ours." They were astonished to see that he was dropping the birds with a rifle.

Bell reportedly shot 1,011 elephants with his Rigby .275 rifles, 200-plus elephants with .303s, 300-plus with his Mannlicher-Schoenauer .256 and many more with .318s, .350s, .416s and at least one .450/.400. Overall he probably killed at least 1,700 elephants "to his own rifle," as it was said.

Bell the retired country gentleman, fit and sharp as he approached 70.

In five years of steady hunting between 1902 and 1907, interrupted only by trips to Nairobi to sell ivory and re-stock his supplies, Bell's average tusk weight was 53 pounds and about 10 percent of his elephants had single or broken tusks. Later on, in the Lado, the average weight dropped to 50 pounds. If his career average was just 45 pounds, and if 90 percent of 1,700 elephants had two tusks, that would have amounted to some 145,350 pounds of ivory. In 1907, Bell was paid 12 shillings per pound of ivory, a figure that might also be a reasonable career average. This would put his gross earnings at about ï½£87,000, of which some 30 percent probably went for overhead: travel, ammunition, guns, camp and trade goods and pay for his native crews. Through the 1930s, a working-class family in Britain could live for a year on ï½£150.

Bell's version of R&R was an infrequent trip home, bringing unusual gifts: "Instead of suit cases, the railway porters had nine- or ten-foot-long slippery tusks to handle. They slid off the barrows, and when they did stay put they raked the mob of baggage-seekers just about knee-high, to their indignation. These tusks that I thus brought home were duly presented to my sisters, who promptly sold them and invested in diamonds."

Bell flew rickety fighter planes in the Royal Flying Corps in World War I over Europe and in South Africa, with all the high adventure one might expect and then some. After the war, he succumbed to both marriage and "Balkan malaria," then returned to Africa for a long and profitable safari along the Niger and Bahr Aouck rivers. But the era of the automobile was dawning. A road-narrow, rutted, dusty or muddy, but nonetheless a road-had been cut through the Karamoja. The great days of Africa seemed over to Bell; now the emphasis was on rushing through the bush as fast as possible. He cashed out and went home.

Apparently Bell returned to Africa just once more, in late 1923, to escort two American half-brothers, Gerrit and J. Malcolm Forbes of Boston, on a motorized safari through Chad and Sudan. He had little to say about the trip in his memoirs other than that their car and lorry caused considerable unease among the native tribes and "as for serious hunting, it was out of the question." They went crashing through the bush at 30 or 40 miles per hour!

Bell and his wife Katie retired to a handsome home at Garve, in the Scottish Highlands about 25 miles northwest of Inverness, on Corriemoillie, her family's estate. They commissioned a steel-hulled sailing yacht, a bluewater racer/cruiser to a design by Olin Stephens, and named it Trenchemer, after Richard the Lion-Heart's red galley. The stories and pencil sketches that Bell had begun many years earlier in Africa now became magazine articles and eventually two popular books, and then a third one after his death. Bell the country gentleman sailed and tramped the hills and hunted deer and rabbits, and continued to do business with Rigby in London. The last Bell entry in the company's ledgers reads:

Wednesday Sept. 5, 1945

Capt. W.D.M. Bell / Corriemoile [sic] Garve. Let him know as soon as we are able to fit a new barrel to one of his .275 rifles & quote price. Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley and Roger Sanger

Excerpted with permission of John Rigby & Co. from Rigby: A Grand Tradition, a 2012 book by Silvio Calabi, Steve Helsley & Roger Sanger. Available from Amazon and other book sellers.

Last edited by a moderator: