African Hunting Gazette

AH member

Hunters of Yesteryear

by Thea Rheeder

Southern Africa’s Early Hunting History: From the Diary of PH ‘Ewart Rheeder’

© B&W

My grandfather, Ewart Rheeder grew up on a farm in South Africa, where he developed a great love of cattle. But he also loved hunting, and while there was plenty of plains-game hunting to be had in the nearby surrounds, he yearned to get amongst ‘the big stuff.’ That was in the 1950s, when a number of big cattle ranches in the southern lowveld of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) had an excess of wild herbivores like zebra and wildebeest, and even buffalo. Because they grazed the grass in competition with the cattle, they were hunted as pests. Ewart set off to find work there.

He was offered a job as a section cattle manager on the vast Liebigs ranch, which was a half million acres with an equally vast population of unwanted wild game. Ewart recorded this serendipitous experience as he and the other section cattle managers were paid a bounty of two shillings and sixpence (Rand value = 25 cents) for every zebra and wildebeest tail they brought to head office. Today we would sniff at such pay, but then a whole gallon of petrol cost about 25 cents!

Elephant tended to break down cattle fences, which allowed the cattle to stray and also caused damage at the watering points at boreholes around the ranch. Like the grazers, they were hunted as pests; they were not shot on licence, and so the tusks had to be surrendered to the game department.

At that time it was illegal to profit from any game shot. In 1933 Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, which were both still under British rule, were signatories to the International Convention of African Fauna, which banned profiting from game in any way. The lop-sided thinking was that if game had a monetary value it would quickly be wiped out. In fact, the exact opposite has proved true. Give a man something to value and, generally, he will preserve and not destroy it.

By the mid-1950s, wildlife outside the protected areas was in serious decline in both countries. South Africa’s black rhino population, reduced to only 12 animals, was on the brink of extinction. Virgin ranch land was being taken up in the heart of the game lands in both countries, and the new owners were expected to shoot out the wildlife to make way for their cattle. But three lowveld ranchers on the Rhodesian side could clearly see the nonsensical thinking behind this. Their land was already at full carrying capacity with natural ‘on the hoof’ protein from game animals, which they had to destroy, at zero profit, because it was illegal to profit from game. They were expected to bring in cattle that had to be bought, fenced, dipped, and, in bad times, fed.

And while cattle were solely grazers, the existing game consisted of both grazers and browsers. Considering that the browsers included kudu, eland and giraffe, all heavy animals, they reasoned that land carrying only wild game must have nearly twice the ‘protein on the hoof’ than the same land carrying only cattle!

The three ranchers who could not see the wisdom of not using ‘natural’ protein for financial gain were the brothers Alan and Ian Henderson, who owned the very large Doddieburn ranch they’d inherited from their father; a portion of the ranch was left entirely for the naturally occurring game. Not far from them was Cecil Style, a newcomer on a large virgin ranch he named Buffalo Range, due to the large numbers of buffalo in residence when he arrived. They teemed up to see Dr. Reay Smithers, author of the wildlife reference book entitled The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion, who was the Curator of Museums of Rhodesia. In 1958 Smithers arranged for two Fulbright scholars from America, Raymond Dasmann and Archie Mossman, to come and examine the feasibility of ranching game instead of cattle, particularly in marginal rainfall areas where game could exist in greater numbers than cattle.

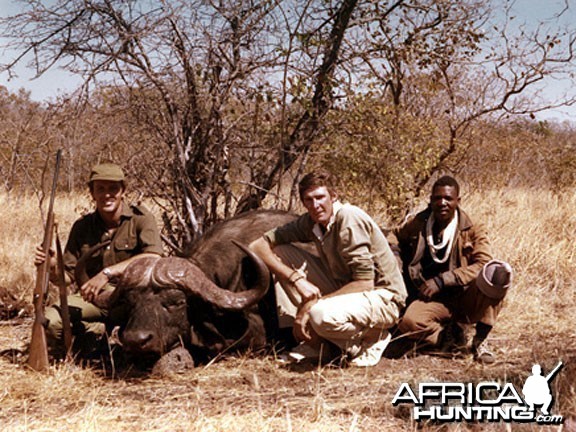

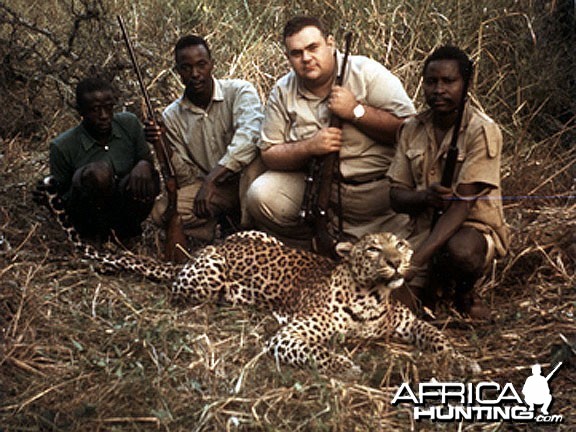

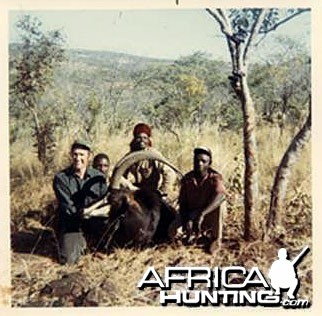

A retired PH dug through his photos and sent us these: a nice leopard taken in the Zambezi Valley in the early 1970s, plus sable and buffalo taken in Matetsi, Zimbabwe.

The brothers gave the scholars open-house on Doddieburn to prove the theory that game can produce more meat per acre than cattle, does not have the expense of being bought, and can be harvested and marketed to butchers in the same way as cattle. And they did. And so, in 1959, the ‘game ranching’ that we see today came into being under the concept of ‘wildlife utilization on a sustained yield basis.’ The naturally occurring game on a rancher’s land could now be harvested and sold, just like his cattle and sheep.

Meanwhile, government ecologists tested rules of what was termed ‘scientific cropping principles.’ These included cropping at night with spotlights from open vehicles and at waterholes with silent rifles. Shooting from a vehicle during daylight was absolutely condemned. Population counting methods were devised, quotas of each species were set, and cropping permits issued. Liebigs ranch very quickly got into the act, and was allocated large quotas of all the species of game on the ranch, which included elephant and buffalo. My grandfather was taken off the cattle and made a permanent game cropper, getting the experience he longed for with ‘the big stuff.’ But there was still a fly in the ointment.

In 1953 Mozambique closed commercial ivory hunting, where professional elephant hunters could buy elephant licences ad lib and live off the ivory they sold, in favour of sport safari hunting. Botswana had also instigated safari hunting. Later, when East Africa closed hunting, a number of the big names in professional hunting - like Harry Selby, Tony Henley and Eric Rundgren – left for Botswana. In Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, although they no longer enforced the ‘no profit from wildlife’ ban, in that it allowed game ranching, profit from sport hunting was not permitted. The reason given was that “sport hunting, and safari hunting in particular, cut through the principles of scientific cropping.”

Rhodesian game ranchers argued that if an animal was to be cropped and its meat and skin sold, why not allow an overseas safari client, who takes only the horns and cape to shoot it in exchange for a fistful of foreign currency? But the Rhodesian government was adamant: Sport hunting on a game ranching permit would never be allowed, and the South African government was obliged to follow suit.

Time went on. My grandfather left Liebigs to work as a game cropper for one of the existing game ranchers at Matetsi at the western top corner of Rhodesia close to the Victoria Falls. He quickly joined the newly formed Game Ranchers’ Association to be elected to the committee that continued to harass the government on this issue. Then the game ranchers in the Matetsi area decided to invite the Honourable PK van der Bijl to a huge dinner at one of the ranches.

PK was the minister of tourism in Rhodesia, and the great, great grandson of Alexander van der Bijl, who is credited with saving South Africa’s bontebok from extinction. He was known to be a big-game hunter of great repute, and was offered a week’s free ‘cropping’ by the rancher where the dinner was held. At first PK refused the offer because, in terms of the cropping permit, only employed personnel were permitted to crop. So the rancher offered him a contract as a temporary employee for one week, in which he had to prove himself eligible for the job at a wage of two shillings (Rand 20 cents) a day, which he gladly accepted.

He duly arrived and enjoyed a week of big-game hunting, at the end of which the dinner was held, attended by 20 guests, all with the chance ‘to pound his ear’ on sport hunting. However, it soon emerged that PK did not need to be converted. He was already a champion of the idea, and while stressing that as minister of tourism, not land, he had no real influence on the outcome of this matter, but would see what he could do.

My grandfather averred that a shrine should be built to PK’s memory, because there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that he was the force responsible for the change in the game department’s tune. At the beginning of 1967 the ban on sport hunting was lifted. That same year, one of the game ranchers at Matetsi ran the first big-game safari ever conducted in Rhodesia and South Africa. The client was an American hunter who was also a member of the Mzuri Conservation Trust, which was responsible for financing boreholes for game after the tsetse fly fences were built in the Kalahari, cutting off a lot of game from water.

Today, sport hunting is recognized by all conservation-minded people as being the strongest tool that wildlife has in Southern Africa. As my grandfather recorded in his hunting diary: “In 1998 the Zimbabwean hunting industry earned US$19.5 million gross revenue, compared to less than US$2.5 million in 1984. Some 2,000 foreign clients spent 22,000 days hunting.”

Keeping that figure high is just as important for the future of Zimbabwe’s wildlife today.

by Thea Rheeder

Southern Africa’s Early Hunting History: From the Diary of PH ‘Ewart Rheeder’

© B&W

My grandfather, Ewart Rheeder grew up on a farm in South Africa, where he developed a great love of cattle. But he also loved hunting, and while there was plenty of plains-game hunting to be had in the nearby surrounds, he yearned to get amongst ‘the big stuff.’ That was in the 1950s, when a number of big cattle ranches in the southern lowveld of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) had an excess of wild herbivores like zebra and wildebeest, and even buffalo. Because they grazed the grass in competition with the cattle, they were hunted as pests. Ewart set off to find work there.

He was offered a job as a section cattle manager on the vast Liebigs ranch, which was a half million acres with an equally vast population of unwanted wild game. Ewart recorded this serendipitous experience as he and the other section cattle managers were paid a bounty of two shillings and sixpence (Rand value = 25 cents) for every zebra and wildebeest tail they brought to head office. Today we would sniff at such pay, but then a whole gallon of petrol cost about 25 cents!

Elephant tended to break down cattle fences, which allowed the cattle to stray and also caused damage at the watering points at boreholes around the ranch. Like the grazers, they were hunted as pests; they were not shot on licence, and so the tusks had to be surrendered to the game department.

At that time it was illegal to profit from any game shot. In 1933 Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, which were both still under British rule, were signatories to the International Convention of African Fauna, which banned profiting from game in any way. The lop-sided thinking was that if game had a monetary value it would quickly be wiped out. In fact, the exact opposite has proved true. Give a man something to value and, generally, he will preserve and not destroy it.

By the mid-1950s, wildlife outside the protected areas was in serious decline in both countries. South Africa’s black rhino population, reduced to only 12 animals, was on the brink of extinction. Virgin ranch land was being taken up in the heart of the game lands in both countries, and the new owners were expected to shoot out the wildlife to make way for their cattle. But three lowveld ranchers on the Rhodesian side could clearly see the nonsensical thinking behind this. Their land was already at full carrying capacity with natural ‘on the hoof’ protein from game animals, which they had to destroy, at zero profit, because it was illegal to profit from game. They were expected to bring in cattle that had to be bought, fenced, dipped, and, in bad times, fed.

And while cattle were solely grazers, the existing game consisted of both grazers and browsers. Considering that the browsers included kudu, eland and giraffe, all heavy animals, they reasoned that land carrying only wild game must have nearly twice the ‘protein on the hoof’ than the same land carrying only cattle!

The three ranchers who could not see the wisdom of not using ‘natural’ protein for financial gain were the brothers Alan and Ian Henderson, who owned the very large Doddieburn ranch they’d inherited from their father; a portion of the ranch was left entirely for the naturally occurring game. Not far from them was Cecil Style, a newcomer on a large virgin ranch he named Buffalo Range, due to the large numbers of buffalo in residence when he arrived. They teemed up to see Dr. Reay Smithers, author of the wildlife reference book entitled The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion, who was the Curator of Museums of Rhodesia. In 1958 Smithers arranged for two Fulbright scholars from America, Raymond Dasmann and Archie Mossman, to come and examine the feasibility of ranching game instead of cattle, particularly in marginal rainfall areas where game could exist in greater numbers than cattle.

A retired PH dug through his photos and sent us these: a nice leopard taken in the Zambezi Valley in the early 1970s, plus sable and buffalo taken in Matetsi, Zimbabwe.

The brothers gave the scholars open-house on Doddieburn to prove the theory that game can produce more meat per acre than cattle, does not have the expense of being bought, and can be harvested and marketed to butchers in the same way as cattle. And they did. And so, in 1959, the ‘game ranching’ that we see today came into being under the concept of ‘wildlife utilization on a sustained yield basis.’ The naturally occurring game on a rancher’s land could now be harvested and sold, just like his cattle and sheep.

Meanwhile, government ecologists tested rules of what was termed ‘scientific cropping principles.’ These included cropping at night with spotlights from open vehicles and at waterholes with silent rifles. Shooting from a vehicle during daylight was absolutely condemned. Population counting methods were devised, quotas of each species were set, and cropping permits issued. Liebigs ranch very quickly got into the act, and was allocated large quotas of all the species of game on the ranch, which included elephant and buffalo. My grandfather was taken off the cattle and made a permanent game cropper, getting the experience he longed for with ‘the big stuff.’ But there was still a fly in the ointment.

In 1953 Mozambique closed commercial ivory hunting, where professional elephant hunters could buy elephant licences ad lib and live off the ivory they sold, in favour of sport safari hunting. Botswana had also instigated safari hunting. Later, when East Africa closed hunting, a number of the big names in professional hunting - like Harry Selby, Tony Henley and Eric Rundgren – left for Botswana. In Southern Rhodesia and South Africa, although they no longer enforced the ‘no profit from wildlife’ ban, in that it allowed game ranching, profit from sport hunting was not permitted. The reason given was that “sport hunting, and safari hunting in particular, cut through the principles of scientific cropping.”

Rhodesian game ranchers argued that if an animal was to be cropped and its meat and skin sold, why not allow an overseas safari client, who takes only the horns and cape to shoot it in exchange for a fistful of foreign currency? But the Rhodesian government was adamant: Sport hunting on a game ranching permit would never be allowed, and the South African government was obliged to follow suit.

Time went on. My grandfather left Liebigs to work as a game cropper for one of the existing game ranchers at Matetsi at the western top corner of Rhodesia close to the Victoria Falls. He quickly joined the newly formed Game Ranchers’ Association to be elected to the committee that continued to harass the government on this issue. Then the game ranchers in the Matetsi area decided to invite the Honourable PK van der Bijl to a huge dinner at one of the ranches.

PK was the minister of tourism in Rhodesia, and the great, great grandson of Alexander van der Bijl, who is credited with saving South Africa’s bontebok from extinction. He was known to be a big-game hunter of great repute, and was offered a week’s free ‘cropping’ by the rancher where the dinner was held. At first PK refused the offer because, in terms of the cropping permit, only employed personnel were permitted to crop. So the rancher offered him a contract as a temporary employee for one week, in which he had to prove himself eligible for the job at a wage of two shillings (Rand 20 cents) a day, which he gladly accepted.

He duly arrived and enjoyed a week of big-game hunting, at the end of which the dinner was held, attended by 20 guests, all with the chance ‘to pound his ear’ on sport hunting. However, it soon emerged that PK did not need to be converted. He was already a champion of the idea, and while stressing that as minister of tourism, not land, he had no real influence on the outcome of this matter, but would see what he could do.

My grandfather averred that a shrine should be built to PK’s memory, because there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that he was the force responsible for the change in the game department’s tune. At the beginning of 1967 the ban on sport hunting was lifted. That same year, one of the game ranchers at Matetsi ran the first big-game safari ever conducted in Rhodesia and South Africa. The client was an American hunter who was also a member of the Mzuri Conservation Trust, which was responsible for financing boreholes for game after the tsetse fly fences were built in the Kalahari, cutting off a lot of game from water.

Today, sport hunting is recognized by all conservation-minded people as being the strongest tool that wildlife has in Southern Africa. As my grandfather recorded in his hunting diary: “In 1998 the Zimbabwean hunting industry earned US$19.5 million gross revenue, compared to less than US$2.5 million in 1984. Some 2,000 foreign clients spent 22,000 days hunting.”

Keeping that figure high is just as important for the future of Zimbabwe’s wildlife today.

Last edited by a moderator: